Sunrise, Sunset, and Moving Swiftly Through the Days

A new month in a new year and it’s gone by far too quickly. I thought I’d close out the lengthening days of January by sharing some interesting sources of information. The pick for today is the NOAA Sunrise/Sunset Calculator, developed by some talented former colleagues. It is a resource used by people in all walks of life—from scientists and sky watchers to film makers and event planners—and a great way to explore what’s going on in terms of the number of hours of daylight received in a day.

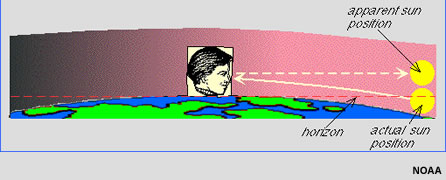

According to the calculator, at 40 degrees latitude in the approximate middle of the mountain time zone, the apparent sunrise on January 31 is 7:09 a.m. and apparent sunset is 5:19 p.m. What’s “apparent” sunrise, you ask? Let’s use this graphic from the solar calculator Help Guide (really guys, great work putting this resource together!) to illustrate:

Earth’s atmosphere refracts (or bends) incoming light from the Sun. Because of that refraction, we see the sun “rise” shortly before it actually crosses the horizon. Likewise, we see the setting sun for a short time after the sun has actually “sunk” below the horizon at the end of a day. (If this part sounds like desperation from a person eager for any at all additional daylight, well, consider that mid-latitude winters sometimes just seem…long.) Apparent sunrise and sunset times are different than actual sunrise and sunset times, adding just that little bit of additional time to the number of hours of daylight in a day.

The nice thing about the end of January sunrise and sunset times is how they differ from the dark, dark days of December. Did we talk about the solstice on December 21? On that day, the apparent sunrise was at 7:18 a.m. but the sun was gone a full 40 minutes earlier, at 4:39 p.m. For those of us desperate enough to grab those few minutes based on apparent sunrise and sunset, 40 minutes seems quite a cause for celebration, or at least acknowledgment. Go ahead, play with sunrise and sunset times for your location, and check out what happens at the summer solstice too.